Barrel, butterfly or slide?

Arguably the most critical part of the interface between man and machine is that of the engine throttle. Designed to restrict the flow of air to the engine by balancing the rate of working of our spark ignition unit against that demanded by the driver, the throttle has evolved and matured over the history of motorsport.

In essence, the options available over this time have been barrel, butterfly or slide, and although slide throttles were very popular at one time their propensity to stick wide open and the pedal efforts sometimes required to overcome the high return spring loads have made them more or less obsolete in anything other than historic racing. For most modern applications the battle is between the barrel and the butterfly as a means of controlling the airflow.

The big advantage of the slide throttle is that in the fully open position there is no spindle to restrict the airflow. Having much the same effect when fully open, these days the barrel throttle has its attractions, and when carefully designed has many of the attributes of the butterfly at part-throttle conditions. It is progressive, easily packaged and can be incorporated into the port, getting closer to the inlet valve without compromising the airflow to the engine. But as engine peak power speeds have risen and optimum runner lengths get shorter it has become increasingly difficult to incorporate barrel throttles into the intake port without affecting mixture preparation at part-throttle with port-injected fuelling systems.

Barrel throttles are also much more difficult to make than the other types. Requiring very close fitting tolerances between the port enclosure and rotating barrel to seal when the engine is idling, and despite their apparent advantages, they can be quite bulky and comparatively heavy compared with the other options.

Of course though, engines don't run at wide-open throttle all the time, and even at a circuit like Le Mans, famed for its Mulsanne Straight and high average speeds, the degree of full throttle accounts for no more than 70% of the lap for LM P1 contenders. For the rest of the lap, driveability is the key, and a system that gives good throttle progression and excellent mixture preparation, controlling the engine to a finer level, is of greater importance. After all, under race conditions the ability to extract the maximum speed from the vehicle through the corner, giving a greater terminal velocity at the end of the following straight, is what wins races.

Under these part-throttle conditions the humble butterfly throttle would seem to have the advantage. For although peak power speeds have risen and the overall length of the intake runner been reduced, in order to ensure complete evaporation of the fuel the optimum place for the butterfly will move up and away from the intake valve, towards the bellmouth. Also, with tapered intake runners, larger throttle plates will be required, proportionately reducing the 'blockage' factor of any spindle, and using the latest in profiled throttle plates aerodynamic losses to the intake flow can be minimised.

With its lack of a spindle, the barrel throttle may at first seem to be the best solution. However, for high-speed engines and those operating at part-throttle for long periods, the humble butterfly without its attendant spindle might still be winning the war.

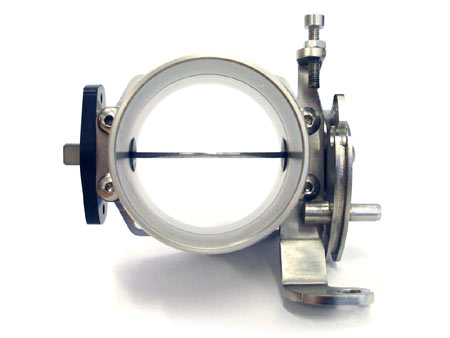

Fig. 1 - The latest in spindleless butterfly throttles

Fig. 2 - Slide throttles on an historic engine

Written by John Coxon