Lift versus Duration

So the next generation of British Touring Cars (BTCC) as far as we know at the moment will be 2.0 litre and turbocharged. Starting in 2011, the engines according to the initial press release, will need to be based on 4-cylinder production units and give something like 300 bhp with a 7000 rpm limit and 0.8 bar boost. Running through an inlet restrictor however, for the first time since 1999, camshafts will we were told, be totally unregulated. Way back then there were no restrictions on the cam lift of the 2.0 litre units and engines were delivering something like 320-330 bhp at the stimulated rev limit of 8500 rpm. Valve lifts were typically something like 15.5 mm (0.610”) and opening durations (from the end of the opening ramp to the beginning of the closing one) were in the region of 280 crank degrees.

So the next generation of British Touring Cars (BTCC) as far as we know at the moment will be 2.0 litre and turbocharged. Starting in 2011, the engines according to the initial press release, will need to be based on 4-cylinder production units and give something like 300 bhp with a 7000 rpm limit and 0.8 bar boost. Running through an inlet restrictor however, for the first time since 1999, camshafts will we were told, be totally unregulated. Way back then there were no restrictions on the cam lift of the 2.0 litre units and engines were delivering something like 320-330 bhp at the stimulated rev limit of 8500 rpm. Valve lifts were typically something like 15.5 mm (0.610”) and opening durations (from the end of the opening ramp to the beginning of the closing one) were in the region of 280 crank degrees.

Although there may be a touch of dewy-eyed nostalgia in all this, at the time camshaft designers had a hard time of it. Given unlimited valve sizes and lift, the skill was to manage the airflow through the engine chasing the maximum airflow past the valve. Since this was proportional to the area under the lift curve, designers would invariably go for maximum lifts in order to keep the cam opening periods short. Short duration cams generally ensure better engine drivability and are as a rule preferable to one with a lower lift but higher duration.

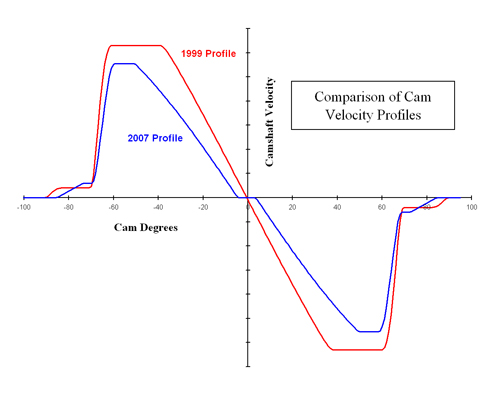

Ten years ago the limiting feature on those 1999 spec engines was the size of the tappet bucket. High lifts and short durations invariably mean high cam velocities which in turn when using flat tappets give high eccentricities and the very danger that the nose of the cam will fall off the edge of the tappet. The solution to the dilemma was to limit the maximum velocity effectively flattening it off (see diagram) but this was only achieved at the expense of increased positive acceleration and increased mechanical loading in the valve train. Fortunately limiting the engine speed to 8500 rpm did help.

When the rules changed in 2000, restricting the cam lift to 12 mm and then 11 mm in 2007, life became altogether easier for the cam designer if probably not quite so for the drivers involved. Although the lift had been restricted, so too in effect had the cam velocity. Stipulating that the tappets would be free, their height and diameter however must be retained. Effectively fixing the diameter to the homologated figure, the rules limited the maximum eccentricity of the cam and hence the velocity. The11 mm lift in recent years has made life so much easier in that the cam is much less likely to reach such high velocities in the first place. Nevertheless, with such a limit greater emphasis is required on opening the valves quickly and keeping them open for a longer period of time. In this way the flow area under the lift curve will only marginally suffer but so too will be the drivability of the engine. Generally reckoned to be delivering something like 285+ bhp, development over the years was probably more down to the detail design of other components rather than just chasing airflow through the engine.

With the move to low boost turbocharged units with intake air restrictors for 2011, depending on the final detail regulations, it certainly looks as though life isn’t to get too onerous for the cam designer. With the air restricted in such a manner there would seem to be little point in going for high lift aggressive cams.

Cam designers should therefore rest easy and look for more challenging opportunities elsewhere.

Written by John Coxon.