Changing the face of Formula One

As the world awaits the new, expected to be revolutionary, engine rules for Formula One, last winter an altogether much quieter revolution was taking place. For tucked away on pages 56 to 58 - towards the back of the 67-page F1 Technical Regulations document - was Article 19, relating to the fuel used in the formula.

As the world awaits the new, expected to be revolutionary, engine rules for Formula One, last winter an altogether much quieter revolution was taking place. For tucked away on pages 56 to 58 - towards the back of the 67-page F1 Technical Regulations document - was Article 19, relating to the fuel used in the formula.

To claim it is a revolution is no hyperbole. For while in both sets of regulations - the 2009 version and its updated 2010 successor - the purpose of the Article is "to ensure that the fuel used in Formula One is petrol as this term is generally understood", the thinking behind the changes goes much further than anyone can possibly imagine even now, some four months into the start of the season.

Since the regulations have changed quite significantly, one might be forgiven for thinking that the fuel raced at Silverstone this year will be radically different from that raced at the same venue last year. To a certain extent this might be true. Since in-race refuelling has now been banned, cars will of necessity have to come to the grid with much higher fuel loads, so the density of the fuel will be more critical.

In addition, since the fuel is now in the car, it can't be kept cool until the pit stop, and its bulk temperature in the vehicle tank will inevitably be higher, particularly later in the race. A higher temperature means more chance of it vapourising in the fuel system unless this is altered at the blending stage.

To counteract these effects the make-up of the fuel, compared to 2009, could be described as 'significantly different'. But a fuel that is 'significantly different' by any stretch of the imagination is hardly one that is revolutionary. After all, it's still gasoline isn't it?

Well, let me explain further. Having said that the fuel at Silverstone this year could be little changed from 2009, the real revolution is in the thinking behind the hydrocarbon components allowed and the changes that could bring about to all of us in terms of sustainable fuel technology at the gas station forecourt.

From 2004 and up to 2009, bio components were introduced to the fuel in response to the ecological conscience of the participants. The FIA wanted to prove to the world with the minimum of effort that the formula was pushing forward the boundaries of fuel technology in terms of lessening the use of fossil fuels.

Introducing a minimum content of 5.75% (by mass) in the form of oxygenates "derived from biological sources" went some way towards defusing any undesirable criticism and shadowed political events in the EU, which at the time were pushing towards even higher levels for forecourt fuels. More important, it bought the FIA and the fuel suppliers time to review their overall objectives regarding the type of fuels used and dovetail them to the possible future demands on the hydrocarbon fuels business. It is no secret that the fuel suppliers look to Formula One as a means of showcasing fuel technology, developing new tools and methods in what is after all a critically important area.

So while other classes of racing moved towards blends of inefficient ethanol, Grand Prix racing saw a future using advanced fuels not too dissimilar to the ones we use today but made up from components that were produced from non-fossil fuel sources. Thus, as rule 19.4.5 in the 2009 regulation simply states that "a minimum of 5.75% (m/m) of the fuel must comprise of oxygenates derived from biological sources", for the 2010 version this has been opened up to include "hydrocarbons and oxygenates". With the relaxation in the distillation characteristics, namely E70° C, E100°C and E150°C, and the abolition of the 'PONA' table, the future could see some very interesting new hydrocarbons derived from biological sources - which of course could eventually benefit us all.

It may be revolutionary but nobody yet knows how much.

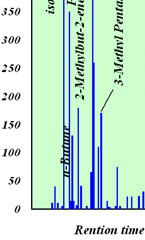

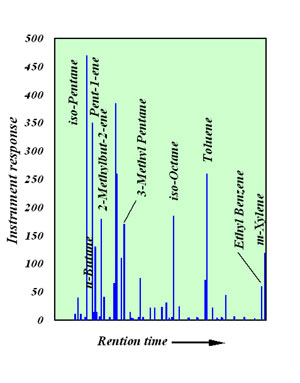

Fig. 1 - The gas chromatogram is designed to 'fingerprint' the fuel but can't distinguish the source of those components.

Written by John Coxon