The intake manifold – wide-open throttle for max power?

Ever since the dawn of the internal combustion engine, it must surely have been self-evident that the most efficient way of introducing the intake charge into the engine is by using a single straight intake tract. The tract may converge slightly to accelerate the flow, and somewhere down its length a throttling mechanism can be included, but in terms of getting the best air distribution across all cylinders this is now the accepted practice.

These days of course we are all too familiar with the concept of multi-point injection and a single runner per cylinder feeding out of a much larger plenum chamber, but believe it or not there were times when this was simply not practical. Designs of this type would invariably need multiple carburettors or, when electronic systems were in their infancy, a single injector per cylinder. Either way, parts were very expensive and therefore mostly unaffordable. All the engine intake air would invariably need to flow through a single fuelling system, and the technology at the time tended to limit the options. So as well as ensuring that the air was evenly distributed across the cylinders, you also had to ensure that the fuel was equally spread as well.

In those days, a single downdraft fixed-jet carburettor would have been placed high up in the engine bay, and the fuel drawn in through the venturi would impinge on the throttle plate below. I say ‘impinge’ because the fuel didn’t so much spray out of the venturi and into the airstream so much as dribble out and, on hitting the throttle plate, disperse into the intake air from this. In more modern times, anyone viewing this process with high-speed video will understand what I mean.

Once more or less in the airstream, the trick was to keep it there, and by a combination of turbulent flow (produced by the often torturous shape of the manifold) and wetting and subsequent evaporation of the fuel from the manifold walls, a charge approaching some form of homogeneity would result.

This was all very good at part-throttle when the air-to-fuel ratio across the cylinders was often fully acceptable. At full throttle, however, the combination of the internal flows in the manifold and the tendency of the fuel to migrate towards the inner two cylinders (of a four-cylinder engine) meant the spread of air-to-fuel ratios across the cylinders could sometimes be up to four or more. Viewed in terms of actual numbers, this would mean that at certain wide-open throttle conditions, when the nominal stoichiometric condition was 14.7:1, at least one cylinder was running at or near 12.7:1 (rich) and another at 16.7:1 (very lean). The tendency for the engine to run into detonation at low speed on the weaker cylinder was therefore very great.

At the same time though, another thing was noticeable – when clear of ‘knock’, and as the throttle was progressively closed, the power of the engine actually increased! Eventually this was put down to a combination of improved mixture preparation and a re-biasing of the air and fuel flows by the single throttle plate, but it just goes to show that you don’t always get maximum power at wide-open throttle.

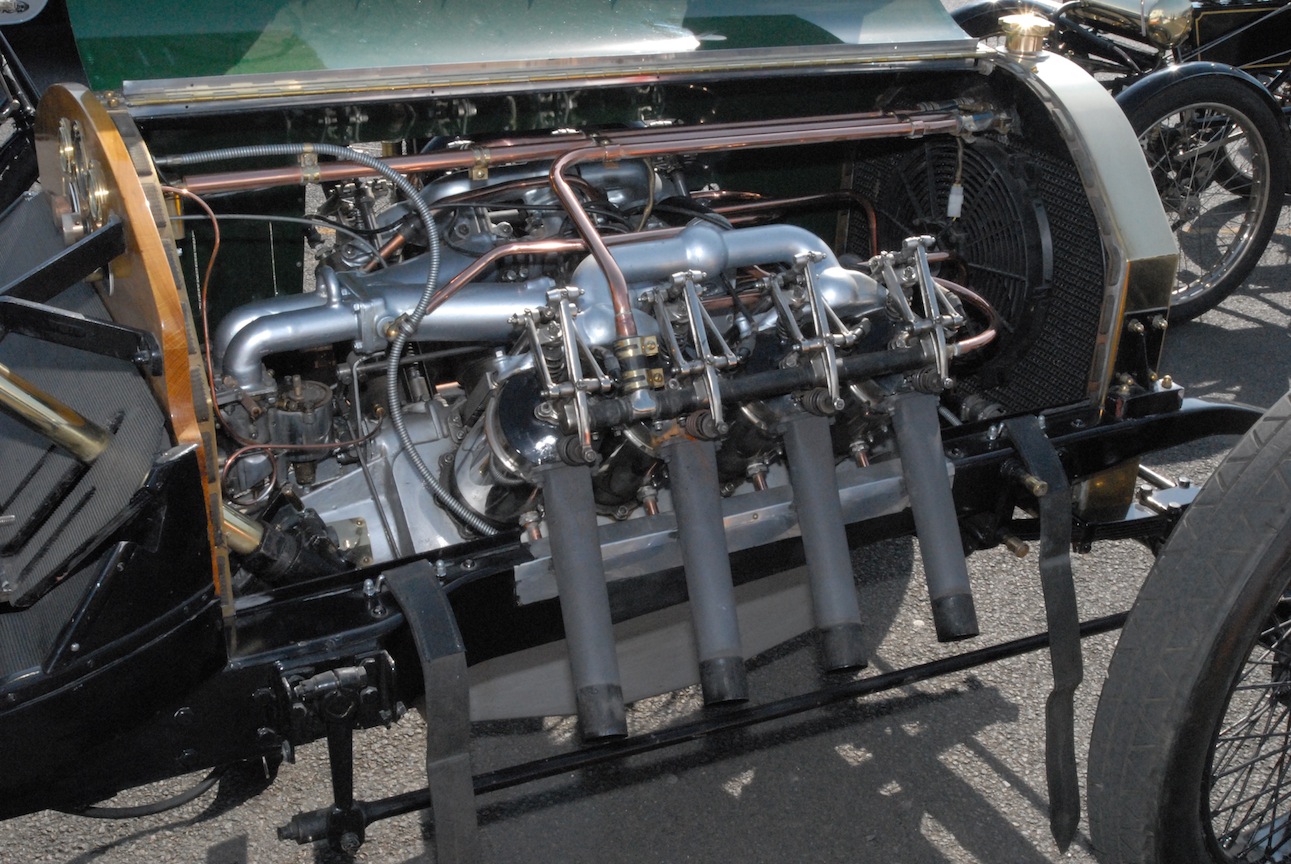

Fig. 1 - An interesting arrangement on this Delage – an updraught carburettor!

Fig. 1 - An interesting arrangement on this Delage – an updraught carburettor!

Written by John Coxon