Oval pistons

For those who don’t follow motorcycle racing or development, there may be interesting things – quite aside from the racing – which you are missing out on. However, even engineers who have a veritable aversion to motorcycles must have tried hard, if they were working in the 1980s or early 1990s, not to notice the development of the Honda oval-piston motorcycles.

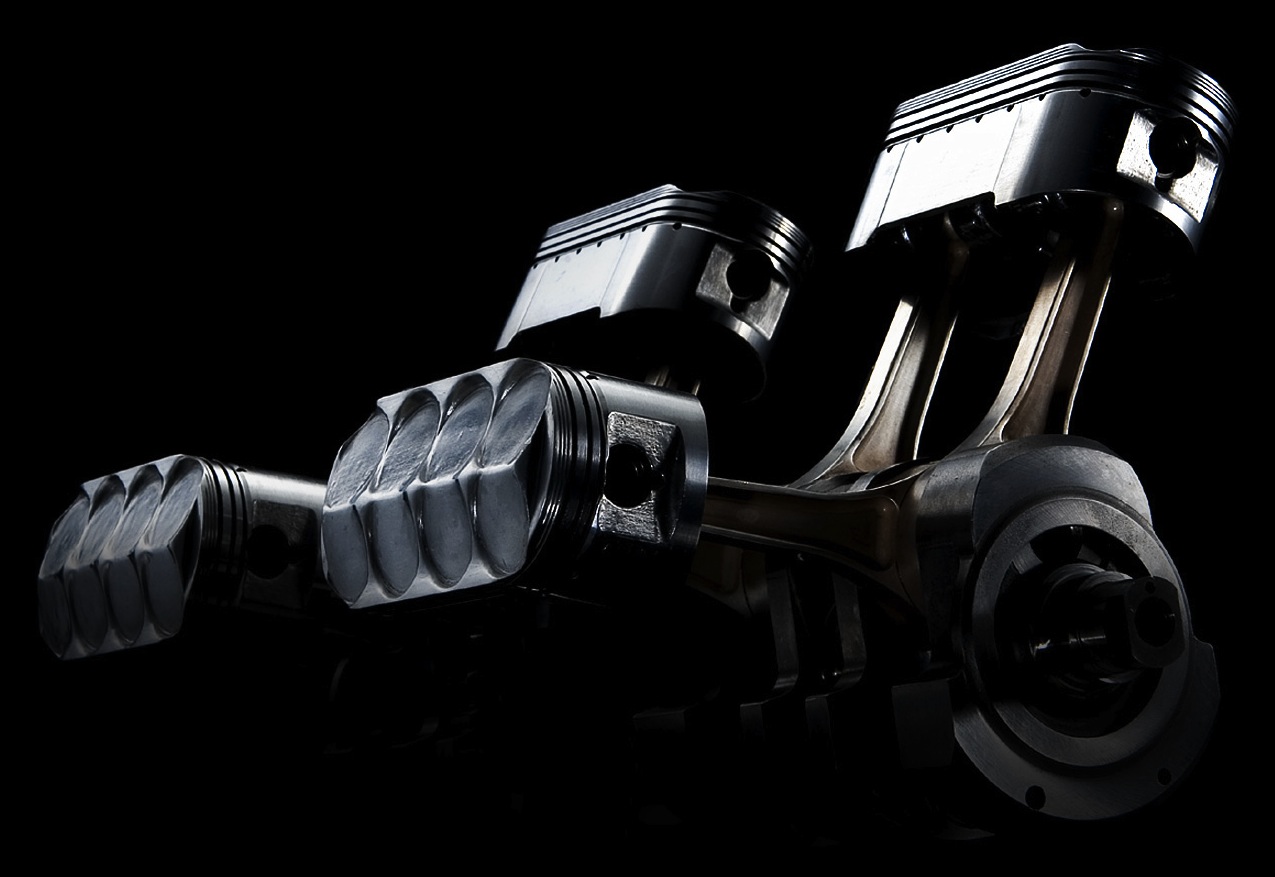

The top class of motorcycle racing had for some time been dominated by two-stroke motorcycles. The capacity limit for the top Grand Prix was 500 cc, and Honda decided – possibly because it would be a difficult engineering challenge – to build a four-stroke 500 cc racer to challenge the dominant two-strokes. What it came up with was the NR500, a machine with a number of innovations, not least of which was a remarkable engine equipped with ‘oval’ pistons. The engine was a V4, which was unremarkable, but it had eight con rods, eight spark plugs and 32 valves, as we might expect in a four-stroke engine with twice the number of cylinders. The engine was essentially a V8, but with four pistons. The crankshaft had four pins, each carrying two rods; continuing with the strange architecture, all four crankpins were coaxial.

The oval piston was not, if fact, oval in the usual sense of the word. If we imagine a circle split in half, with the halves moved apart and a rectangular section inserted tangentially to the separated halves of the circle, this is the actual shape. The aspect ratio of the piston – that is, the ratio of piston length to width – is defined by the number of valves and their size/disposition. In the case of the various Honda oval-piston engines, including the NR500 and both road and race versions of the NR750, each cylinder had four inlet and four exhaust valves.

The greatest technical challenge was perhaps not in the manufacture of the piston, but in making the piston rings work. We know instinctively from handling piston rings, and perhaps from design studies, that squeezing a ring creates a ring tension that is pretty even around the cylinder bore. One can imagine that trying to create the same effect for a piston ring with a distinctly non-circular profile would present a huge challenge.

According to Cameron*, the original skirt piston profile with its flat sides was eventually replaced with one whose curvature was more continuous, as in two ‘ends’ with small radii joined by ‘sides’ of large radii. Allegedly, one strategy for piston rings was not to have a single ring per groove but to have two overlapping ‘half rings’. Piston development was also rumoured to have incorporated a period of magnesium piston development. Honda has not been alone in trying to use magnesium pistons in race engines.

The oval-piston project was not a great success. Against the might of the other manufacturers and their well-developed two-stroke technology, the Honda NR500 struggled. Its only race win was a non-championship 500 km race in Japan. On the Grand Prix circuits, the highlight of the bike's career was to run in fifth position in the 1981 British Grand Prix before breaking down; its highest Grand Prix finish was 13th. It did however spawn a wonderful 750 cc oval-piston endurance racer, and an incredibly expensive 750 cc road bike.

* Cameron, K., “Classic Motorcycle Race Engines”, Haynes, 2012, ISBN 9-7818-4425-9946

Fig. 1 - Oval-piston engine internals (Courtesy of Honda)

Fig. 1 - Oval-piston engine internals (Courtesy of Honda)

Written by Wayne Ward