KERS put to the test

RET recently attended the 2009 UK Formula Student competition at the Silverstone circuit in Northamptonshire.

RET recently attended the 2009 UK Formula Student competition at the Silverstone circuit in Northamptonshire.

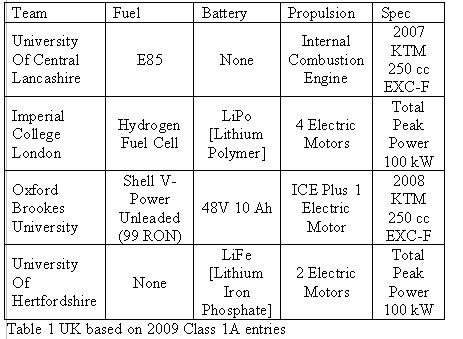

Of the total 87 teams from 16 countries, seven were in Class 1A, of which four were from the UK. Class 1A is the competition’s low carbon category. Teams are encouraged to use green technology and alternative fuels to reduce their CO2 emissions. In an additional challenge, the teams calculate the CO2 and energy that are used during manufacture of the car. Teams compete in all dynamic and static events but are judged on their car’s sustainability rather than cost.

Under Formula Student rules the first 50% of brake pedal travel may be used for energy recovery. This is potentially important in Class 1A as the cars performance in the endurance race is evaluated by measuring the mass of CO2 produced.

The three teams which carried batteries for on-board energy storage all had the potential to use regenerative braking. University Of Hertfordshire ran a fully electric car in 2009 but decided not to use regenerative braking during the event despite having the potential to do so.

James Major, Herts’ Team Leader in the Class 1A car, told RET Monitor;

“We decided in advance not to use regenerative braking as we calculated that due to the low mass of the car (Herts’ Class 1A car came in at an impressive 260 kg), and the low speeds attained during the event, the potential amount of recoverable energy would not justify the time required to develop and test the system. This is despite the fact that our controller is very capable of managing a regenerative braking system.

“Post event analysis of the on board data acquisition system indicated that we could have recovered around 3% of the total energy which was consumed during the event. Whilst that doesn’t sound like much, 3% is a very worthwhile gain in such a closely competitive environment – imagine if one of the Class 1 cars was allowed a 3% increase in restrictor size!

“Really though, the main benefit for us would be if regenerative braking allowed us to reduce the on board battery capacity, as that would obviously reduce vehicle mass.”

Imperial Racing Green, from Imperial College, unfortunately ran out of time to pass scrutineering and therefore were not allowed to race their extremely innovative and ambitious Hydrogen fuel cell car.

Siten Mandalia, Chief Engineer, told RET Monitor;

‘We run an electric motor on each wheel and a major reason for doing this is energy recovery from braking. Our go kart project uses regenerative braking on the rear wheels only; experience with this tells us we should be looking to recover 20 to 30% of total input energy – although it’s very difficult to calculate accurately and would need track testing. Safety rules limit the rate at which we can charge batteries, so for next year we aim to have a bank of super capacitors in place.”

Oxford Brookes University’s petrol-electric hybrid Class 1A car also ran without regenerative braking. James Larminie, an Engineering Lecturer in OBU’s Mechanical Engineering Department explains;

“Since only the back axle can be used, the benefits are very limited, and there is great danger of locking the back axle. I think this is liable to be so for all very light vehicles. This was shown at the all electric motorcycle race which was part of the Isle of Man TT. I don't think any used it, except for one, who crashed. Regenerative braking only really comes into its own for heavier cars, buses and delivery vehicles.”

In Class 1, the premier category, in which cars are powered by 600 cc four stroke engines fuelled by either petrol or E85, current rules do not allow energy recovery systems.

Formula Student teams have clearly come to the conclusion that energy recovery is, as the regulations stand, of limited benefit and therefore does not justify the investment of time and money.

Written by Tom Sharp.