Radiators

The design of the vehicle cooling system on a racecar is a comparatively simple task, provided a number of basic facts are truly understood. So after the positioning of all the other major components in the vehicle, the engine, the gearbox – and of course the driver – somewhere in the remaining space will eventually dictate the position of the radiator, and for practical reasons (like the need to supply copious quantities of cool air) this is normally placed adjacent to the external bodywork.

The first point to remember in any design is that the density of hot water is less than that of cold water. At 90 C, a temperature typical of the top of a vehicle radiator, the density of pure water is 965.163 kg/m3. At 85 C, a typical temperature at the base of the radiator, this increases to 968.508 kg/m3, an increase of 3.3 kg/m3. While this difference is relatively small, the natural tendency of the cooling medium will still be to sink towards the base of the radiator, allowing hotter fluid from the engine to take its place.

On the other side of the engine cooling system the cold water circulating through the engine will pick up heat and rise up, passing through the cylinder head and into the top hose. If this hose is linked directly to the top of the radiator then the combined effect is to generate a circular motion of cooling fluid sometimes referred to as a thermo-syphon. To speed up the process we also normally add some form of water pump to work along with and in the same direction as this thermo-syphonic action, when any attempts – however small – to work against this natural order of things will compromise any cooling system to a certain degree. Ensuring that the engine outlet hose is linked to the top of the radiator(s) without air locks or sudden changes in overall flow area, and that the radiator outlet hose feeds back into the base of the engine (via the water pump), is therefore a golden rule.

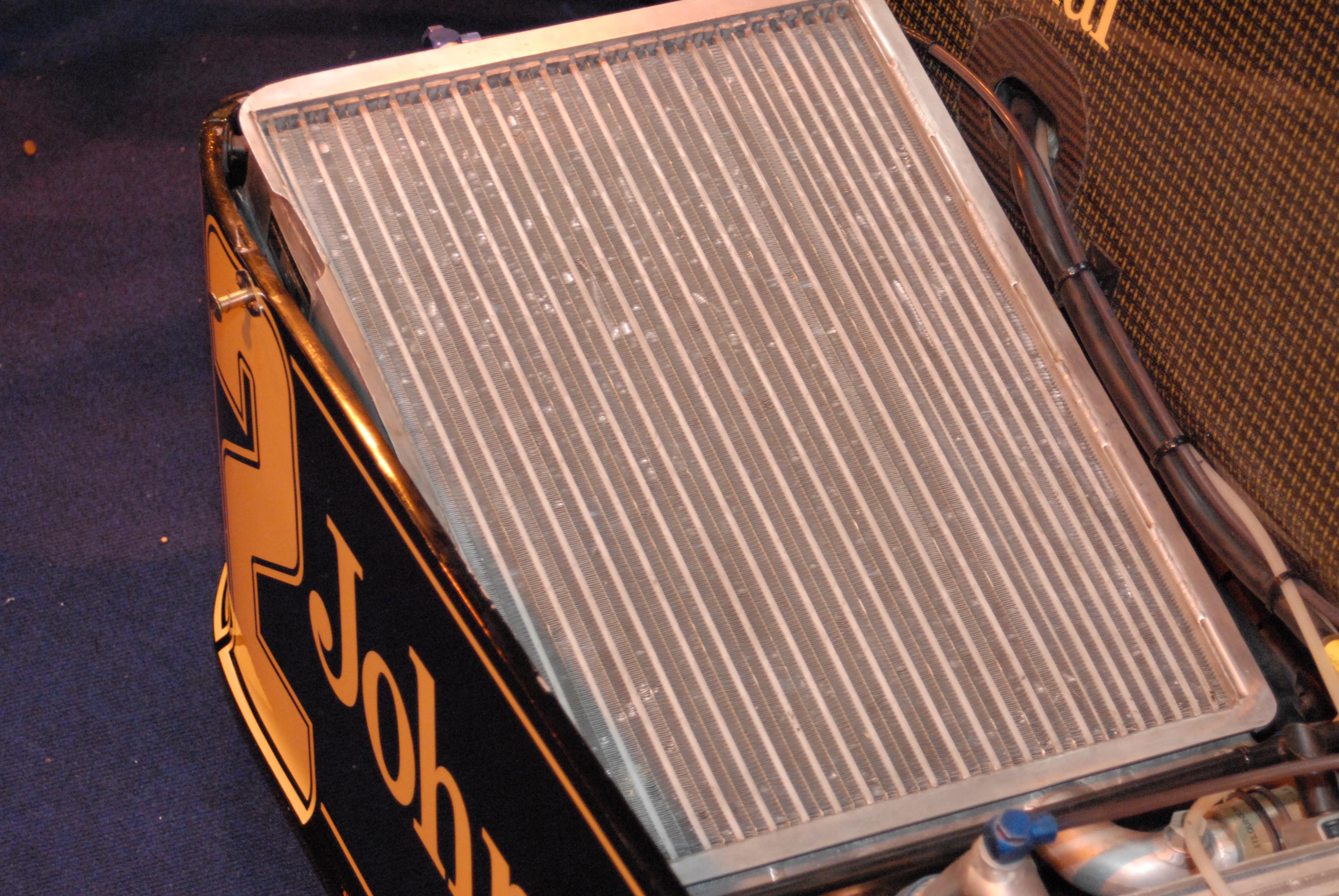

Another point to remember is that the most economical radiator design is one with the narrowest of matrix depths and therefore, for a given level of heat dissipation, the greater the frontal area of the radiator then the more efficient it will be. As radiators fall in cross-sectional area and become thicker, their efficiency also falls, because as the air passes through it picks up heat and the temperature difference between it and the medium to be cooled – so essential to the process – will be reduced. In many racers this is evidenced by very large but thin radiators being laid down at an angle to the direction of flow. This reduces the cross-sectional area exposed to the direct flow of air but also has the effect of lowering the centre of gravity – so essential for other aspects of vehicle dynamics.

When requiring the best radiator design to be used it also makes sense to ensure that the radiator itself is cooled in the most efficient way. Making sure that the cooling air is properly ducted to and from the radiator, and that all cooling air is encouraged to pass through it rather than around it, are all also important. Smooth internal ducting converging slightly to accelerate the flow of cooling air is therefore essential for best results.

So while the design of the radiator itself is important, to dissipate the heat efficiently, so are many other aspects of the installation.

Fig. 1 - Formula One Lotus Renault turbo radiator installation (Photo: John Coxon)

Written by John Coxon