Rolling along

In the search for ever lower engine friction, it is surely a wonder that the rolling element bearing hasn't featured very highly in recent years. So while ball or roller bearing technology is commonly seen in many engine ancillaries - for example, pumps, starter motors/generators, timing belt tensioners, rocker arms and now even turbochargers - the largest source of rotation friction, that of the crank and camshaft, have largely been avoided. I know two-stroke engines have, and continue to use, needle roller and ball assemblies throughout - principally, I would guess, because the application makes it a necessity (as in the lube requirements of the little end) and technically it is not that challenging - but in the world of high-performance four-strokes, rolling-contact bearings have never in recent years been truly favoured.

In the search for ever lower engine friction, it is surely a wonder that the rolling element bearing hasn't featured very highly in recent years. So while ball or roller bearing technology is commonly seen in many engine ancillaries - for example, pumps, starter motors/generators, timing belt tensioners, rocker arms and now even turbochargers - the largest source of rotation friction, that of the crank and camshaft, have largely been avoided. I know two-stroke engines have, and continue to use, needle roller and ball assemblies throughout - principally, I would guess, because the application makes it a necessity (as in the lube requirements of the little end) and technically it is not that challenging - but in the world of high-performance four-strokes, rolling-contact bearings have never in recent years been truly favoured.

If you go back in history, ball or roller technology was a common sight. Before World War I, the leader in four-valve overhead cam engine design, the Peugeot L3, used ball races on the three main bearings of this four-cylinder unit. The big-end bearings were reserved for plain white-metal bearings but by this action the design intention, I think, was made clear.

Later on, in the mid-1950s and even when 'modern' thinwall steel-backed shell bearings were readily available, Mercedes-Benz still committed to a system of roller bearings on all main and big-ends. Here the multi-piece crankshafts necessary to take the roller system were assembled together using the Hirth process - a system of radial serrated journals clamped together axially by large screws. Even in 1970, legendary engine designer Mauro Forghieri is reported to have preferred roller bearings on the four main bearings of the 312B but eventually settled for just two, one at either end of the one-piece crankshaft.

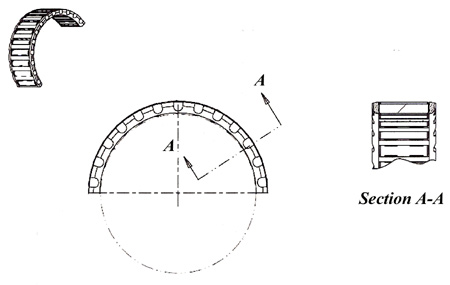

Clearly the issue is the crankshaft and the strength of multi-piece units to enable assembly with the traditional roller bearing. In theory at least, the rolling point contact of the roller bearing over the sliding technology of a more traditional approach should give a significant advantage, and is perhaps why bearing manufacturers are now beginning to look at the concept again. The major difference over earlier designs is the development of split roller technology, which can be readily assembled around traditional one-piece forged or machined-from-solid crankshafts.

Analysis of friction within the traditional internal combustion suggests that around 20% comes from the main and a further 10% from the remaining big-end bearings. This comes from the drag induced in the oil film within the bearings and the high oil pressure needed to generate it. Rolling contact bearings, by their very nature, have considerably less friction, and since they do not require anywhere near as much lubricating oil they should therefore have a significant advantage.

It has been calculated that the friction of a roller bearing is around 10% of that of a traditional bearing at about 3000 rpm. If this holds true on the test bed then the FMEP (Friction Mean Effective Pressure) due to the bearings of an engine of 0.4 bar on an engine at 6000 rpm could be reduced to much nearer 0.1 bar or less - a small but nevertheless useful increase of around 2% in net power output.

In practice, however, no such advantages have been observed yet. Even with significantly reduced oil flow, the action friction measured is equivalent only to that of the best designed shell systems, which is particularly surprising. Clearly, modern shell bearings are much more efficient than many of us are aware and, after factoring in the extremely high levels of durability now expected, these apparently simple devices are highly underrated.

Fig. 1 - Typical Split bearing cage

Written by John Coxon