The fuel pump

The function of the fuel supply system in the spark-ignition engine is simple: to supply the correct volume of fuel at the correct pressure appropriate to the method of engine fuelling used. In the case of a carburettor, for instance, this might mean a fuel pressure of no more than 1.5-2 psi (10-15 kPa) pumping the fuel into the carburettor float chamber, from which the fuel will be sucked into the intake air stream. A simple, engine mounted, cam-actuated mechanical lift pump using an oscillating diaphragm might therefore be the favoured approach, but with more remote, low-mounted fuel tanks and high ambient temperatures, fuel vaporisation can be a problem. Low-pressure electric pumps mounted next to the fuel tank in this case may be a better solution. More often than not, these will still be of the diaphragm variety but operated by safer and more reliable solid-state electronics.

For port-injected engines the role of the fuel pump is more complex. Designed to supply full engine fuel flow rates at anywhere between 60 and 200 litres per hour at a constant pressure above that of the manifold intake, the pump also needs to be operated independently of the engine for events like cold starting or when the engine has stopped – as in the case of a shunt, for instance. Typical rail pressures will be of the order of 3-6 bar (45-90 psi), and one of two types of pump were traditionally used when they were more commonly mounted inside the fuel tank and integral with fuel filters.

The first was a positive displacement pump, but instead of a reciprocating diaphragm, roller cells or simple internal gear pumps would be used. These could deliver the high pressures necessary and be relatively insensitive to fluctuations in the voltage supply. Unfortunately, these pumps also produced high-pressure pulses inside the fuel rail that could influence the injector metering, so more modern electric pumps are more likely to be of the ‘flow’ type. Flow-type pumps use a complex, impeller-based system that slowly but incrementally increases the fuel pressure as the fuel progresses steadily through it. Since this pressure builds up steadily within the unit, the flow is practically pulsation-free, giving a huge advantage over other pumps.

However, when it comes to direct-injection systems, where the fuel is injected directly into the combustion chamber, the pumps tend to be very different. While an electric pump may still be used to scavenge the vehicle fuel tank and introduce the fuel to the low-pressure rail, a further high-pressure system is necessary to get it to the delivery pressure necessary to inject it into the combustion chamber. In such cases, and to increase the pressure from 3-5 bar up to 150 -200 bar, we have to revert to a mechanical system operated from the engine camshaft.

During the evolution of gasoline direct-injection systems, development has followed similar trends in the port-injected world such that systems can be either continuous delivery or demand controlled. The former are more suitable for racing applications since the quantity to be delivered is proportional to the rotational speed, and with as many as three barrels per pump positioned at 120º to each other around the camshaft drive, there is minimal fluctuation in outlet pressure. Compared to demand-controlled systems using a single barrel per cam, there is also little need for low-pressure pulsation attenuation systems. With the maximum fuel delivery configured to that of the maximum demand of the engine, any excess fuel not required is returned to the suction side of the pump, with the high-pressure rail remaining at a constant and hopefully pulse-free pressure.

The pressures may have increased but the development from carburettors to direct-injection fuel systems still need to address many of the same issues.

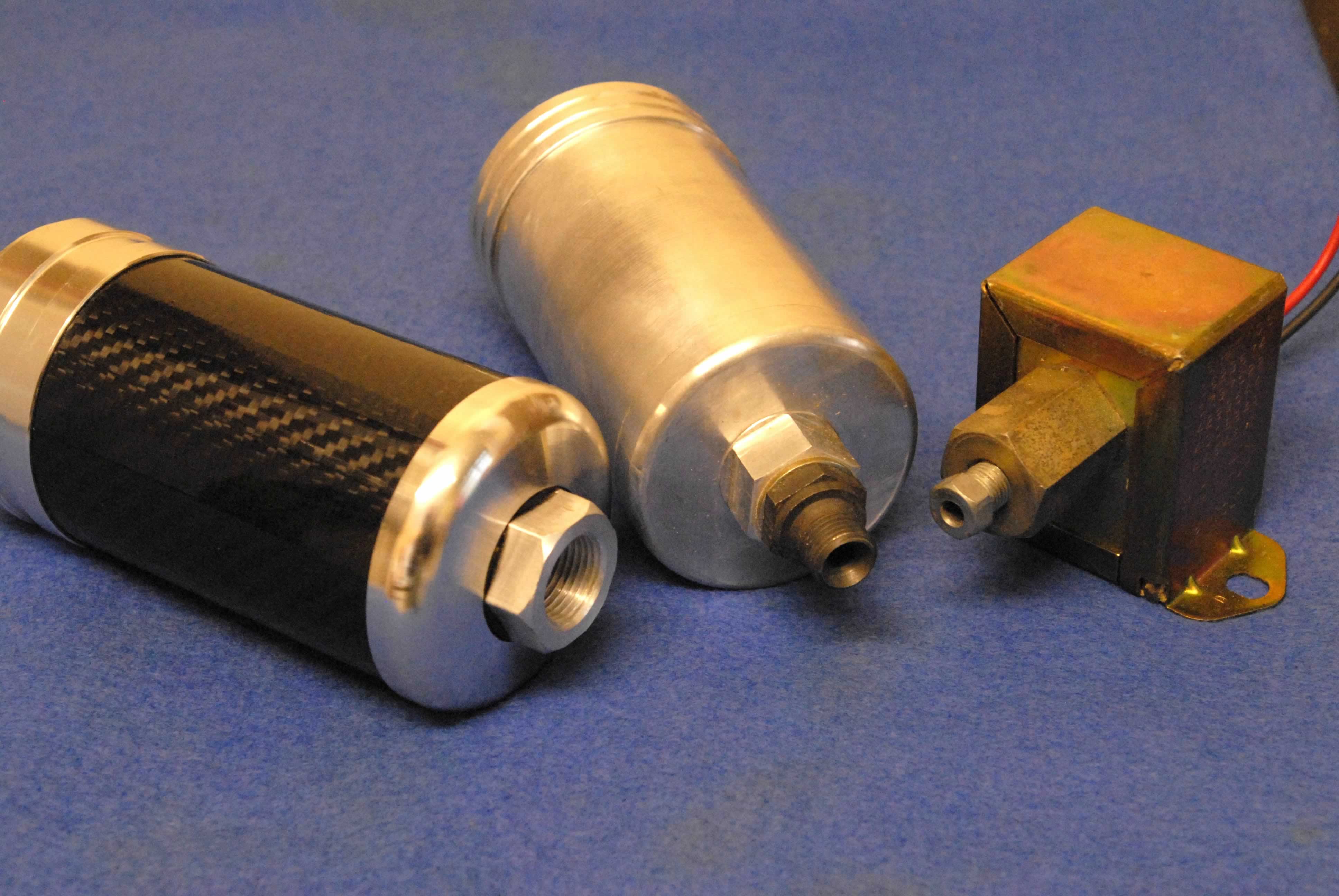

Fig. 1 - A selection of low-pressure fuel pumps

Fig. 1 - A selection of low-pressure fuel pumps

Written by John Coxon