Splitting crank pins

Opinion is divided on the need to have even firing intervals for engines. With very few exceptions, road vehicle engines fire at equal intervals, while many two-cylinder engines fire at unequal intervals, and some three-cylinder engines in the past have also had some very odd firing orders.

The current Yamaha R1 is a four-cylinder engine that has made use of a cruciform crankshaft to give an uneven firing order. This was based on the successful YZF-M1 MotoGP race bike that enjoyed world championship success with Valentino Rossi and Jorge Lorenzo. Whether this is a real benefit for the road motorcyclist or the racer is unclear. Would Rossi and Lorenzo have enjoyed so much success with a flat-plane crankshaft in their bike? I would suggest that they would have been equally successful.

It seems similarly wrong to suggest that Yamaha would encumber their MotoGP bikes with unnecessary complication. Perhaps the riders prefer the feel of such machinery. You will have noticed that uneven firing in production vehicles is mainly restricted to motorcycles. Such machines are rarely designed with smoothness in mind, and one might argue that an uneven firing order adds to the aural appeal of a motorcycle.

Roadcar manufacturers, on the other hand, have no truck with such uneven firing orders - smoothness and lack of vibration and noise are highly valued. There are some vee engines where even firing would not be possible if the rods were run on shared crankpins. A good example of this are the 90º V6 engines used by a number of manufacturers. These are used either because the manufacturers have a 'modular' engine family with a 90º vee angle, or by design because a 60º vee is felt to give too tall an engine, and a 120º angle is either too wide or does not package nicely in a vehicle. For a V6, both 60º and 120º three-pin crankshafts give even firing intervals.

For those who choose to run such production-based V6 engines in their racecars, when a racing crankshaft is manufactured a choice has to be made whether to carry on with a split-pin crankshaft or commission a three-pin crankshaft. The split-pin option is more expensive as it has three extra crankpin grinding operations, but allows other pieces of hardware and electronic circuitry to be retained. The engine control unit would need to be reprogrammed if changing to a three-pin crankshaft - we don't want half of the engine firing 30° early or 30° late.

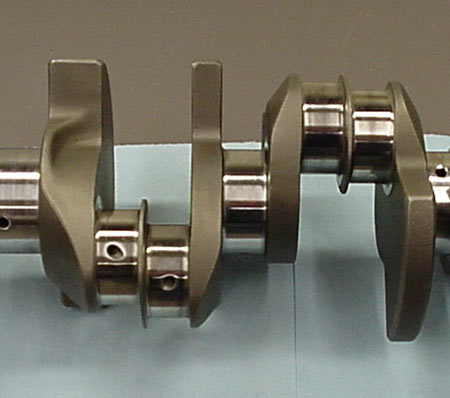

Where a pushrod V6 is concerned, switching away from the even-firing split-pin crankshaft would require new camshafts to be commissioned as well, owing to the fact that, between the adjacent rods, we need to provide space for a 'flying web' to bridge the two pins. We also need room between the two adjacent big-end bearings for fillets.

In providing for the flying web and the pin fillets, the 'bank stagger' is the limiting factor. A very compact engine will have less bank stagger and thus less opportunity to provide wider bearings. It is easy to see that with a split-pin crankshaft we might become limited on rod bearing width, and this might dictate the maximum state of tune of the engine.

Fig. 1 - The space left by the bank stagger has to accommodate 'flying webs' and fillets

Written by Wayne Ward