All screwed up

As an engineer you must always be looking to improve the product, whether it be to improve its performance, increase reliability or simply make it easier and hopefully cheaper to manufacture. The general term for all this activity is development, and although now a dirty word in any engineering organisation - since it implies that the design wasn't correct in the first place - the sealing of the combustion gases at the split line between the cylinder liner and fire face has always been the subject of much of this activity.

As an engineer you must always be looking to improve the product, whether it be to improve its performance, increase reliability or simply make it easier and hopefully cheaper to manufacture. The general term for all this activity is development, and although now a dirty word in any engineering organisation - since it implies that the design wasn't correct in the first place - the sealing of the combustion gases at the split line between the cylinder liner and fire face has always been the subject of much of this activity.

Today we take it pretty much for granted that gas filled 'wills' rings or beryllium copper crush rings will solve the problem. But these require large studs feeding through the cylinder head, compromising not only the design of the water jacket therein but also producing high tensile loads where they locate in the cylinder block. One method of getting around all this is to discard these sealing rings and put the steel or cast-iron cylinder liner into compression, forcing it against the soft aluminium of the fire face on the cylinder head and dispensing with the seal. This has been achieved over the years in a number of ways.

One method is to use long cylinder head bolts. Passing through the cylinder head and then block, and anchoring into the main crankshaft bearings, they put the whole of the cylinder block into compression and clamp the liner flange at the top into compression. Successfully achieved on a number of prototype engines, the design still requires design compromises in the cylinder head water jacket to accommodate the long bolts as well as dictating the position of the bolts around the bore by the position of the main bearings. The Alfa Romeo Tipo B Grand Prix engine of 1932 used a slightly different method by clamping the liner into compression against the bottom face of the cylinder block of the monobloc construction.

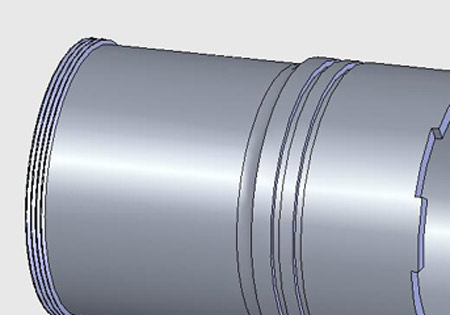

Reasonably satisfactory but not necessarily foolproof, the technique used in later Grand Prix Alfas, used a different sealing method. Starting with the Type 158 of 1938, a single-stage Roots-type supercharged straight eight, the thin-walled steel liners were screwed into the aluminium alloy combined block and head, monobloc casting. Restorers of these classic engines tell interesting tales. With a 'twelve thou' (0.012 in, 0.3 mm) interference fit, the liners have to be cooled in liquid nitrogen complete with tooling, and the monobloc warmed in an oven before assembly can begin. A two-man job, assembly is fairly straightforward, but should things go wrong or the liner jamb part way in, the whole casting risks being scrapped. Ouch!

Used on Grand Prix Alfas until the early 1950s, screwed-in liners can also be found on the unsupercharged, Lampredi-designed 4.5 litre V12 Ferrari engines of the same period. Once again, combining the cylinder head and block water jackets, the thin-wall steel liners, threaded at their upper end, passed up through the open bores of the bottom of the water jackets and screwed into matching threaded bosses surrounding the combustion chamber. Projecting out of the base of the water jacket/cylinder head casting and sealed by a pair of simple O-rings, these liners located directly into the crankcase.

Much nearer to the present day, John Judd used screwed-in liners in the 1996 Grand Prix OX11A Judd-Yamahas. Claiming reduced bore centres and a simple but stiff water jacket, free of stud bosses, the engine weighed 99 kg without wiring loom and ECU.

With a maximum engine weight limit in Formula One, improved parent metal bore coating technology and the many difficulties associated with casting, to my knowledge screwed-in liners have once again been confined to the realms of history. Pity.

Fig. 1 - Screwed-in liner

Written by John Coxon