On-track analysis of rival cars

On-track running is obviously of vital importance to Formula One teams, allowing them to gather real-world data on which to base and validate their performance simulations. However, beyond their own cars, teams are also interested in what the competition is up to and, as such, are always on the look-out for any ideas they may have missed during their own development processes.

A lot can be gleaned simply by looking at the cars as they sit in the pit lane, for example McLaren’s ‘mushroom’ rear wishbones in the 2014 season. But obtaining quantitative data on the competition can be trickier. In the world of production cars, a manufacturer will often buy a competitor’s vehicle to assess the technology it contains, but this is clearly not feasible in Formula One. Teams therefore need to be a little more creative.

For example, before on-track data was recorded and displayed by the governing body for TV audiences, teams would use audio analysis techniques to ascertain the revs the cars were reaching at various points on the track. This could then be combined with speed data gathered by someone trackside using a speed gun, and factors such as likely gear ratios calculated.

The widespread availability of handheld thermal imaging equipment, and even the images generated by thermal cameras as part of the current TV coverage, can provide an insight into the way a particular car is using its tyres. For example, by recording the tyre surface temperatures using a camera at a specific part of the track, comparisons can be made between cars. Also, by looking at variations in surface temperature distributions, teams can combine that with other analysis and data gathered from their own on-car sensors to begin to see how the opposition may be working their tyres.

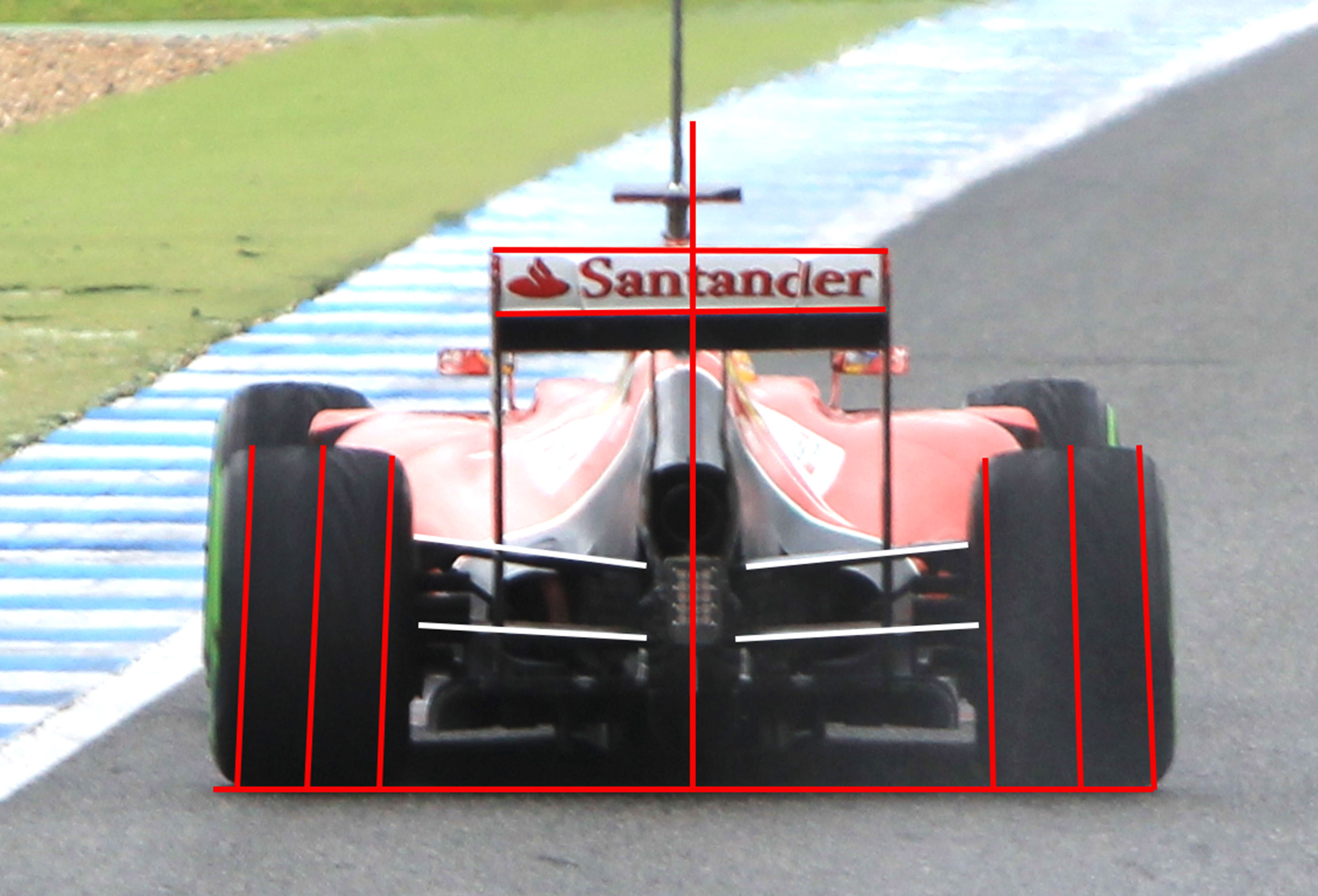

Image analysis can also provide a considerable volume of information. Using still images, known reference points on the car can be taken, and from these the orientation of other components can be studied. For example, if a known vertical plane can be established at the rear of a car, then the camber of the rears wheels can be estimated, as can the roll attitude of the body. Fig. 1 below shows how this is achieved, though it should be noted that this is a quick Photoshop mock-up, albeit based on a real team’s analysis imagery.

Taking this a step further, capturing stereoscopic images can help to understand the relationship of one part of car to another, particularly when it comes to suspension or aerodynamic components. This information can be fed into a CAD package, and from it 3D approximations of components created, revealing useful information such as suspension geometry and relative component sizes. Although it is not known whether any teams have used such devices, compact handheld 3D laser scanners capable of millimetre-accurate measurement are commercially available, and if someone could devise a means of using one in the pit lane without being noticed, no doubt the data gathered would be very revealing.

Video footage, either captured by the a team trackside or from the readily available TV feeds, is another useful analysis aid. By comparing footage of competitors’ cars taken from a fixed position to their own (for which they have real-world data), factors such as corner entry speed, differing racing lines and braking points can all be ascertained. Teams have even used high-speed cameras trackside to deduce factors such as wheel slip rates, by comparing the difference in rotational angles between front and rear wheels.

There a undoubtedly many other cunning methods used by teams to get the measure of their opposition, all of which will be fed back into the overall car development programme for assessment. While understanding how a competitor’s car works will not win a team races, it is important intelligence when combined with a thorough and verified understanding of their own car. As Sun Tzu, the 5th century Chinese military strategist, said in his seminal work The Art of War, “If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles. If you know yourself but not the enemy, for every victory gained you will also suffer a defeat. If you know neither the enemy nor yourself, you will succumb in every battle.”

Fig. 1 - Basic trackside photography can be used to calculate factors such as approximate camber and roll angles (Composite image: Lawrence Butcher)

Fig. 1 - Basic trackside photography can be used to calculate factors such as approximate camber and roll angles (Composite image: Lawrence Butcher)

Written by Lawrence Butcher